Technological History

The presence of glasses in our everyday environment is so common that we rarely notice their existence. Our current casual attitude toward the family of materials known as glasses has not always existed. Early Egyptians considered glasses as precious materials, as evidenced by the glass beads found in the tombs and golden death masks of ancient Pharaohs. The cave-dwellers of even earlier times relied on chipped pieces of obsidian, a natural volcanic glass, for tools and weapons, i. e., scrapers, knives, axes, and heads for spears and arrows. Humans have been producing glasses by melting of raw materials for thousands of years. Egyptian glasses date from at least 7000 B.C.

How did the first production of artificial glasses occur? One scenario suggests the combination of sea salt (NaCl) and perhaps bones (CaO) present in the embers of a fire built on the sands (SiO2) at the edge of a saltwater sea (the Mediterranean), sufficiently reduced the melting point of the sand to a temperature where crude, low quality glass could form. At some later time, some other nomad found these lumps of glass in the sand and recognized their unusual nature. Eventually, some genius of ancient times realized that the glass found in the remains of such fires might be produced deliberately, and discovered the combination of materials which led to the formation of the first commercial glasses.

The first crude man-made glasses were used to produce beads, or to shape into tools requiring sharp edges. Eventually, methods for production of controlled shapes were developed. Bottles were produced by winding glass ribbons around a mold of compacted sand. After cooling the glass, the sand was scraped from inside the bottle, leaving a hollow container with rough, translucent walls and usually lopsided shape. Eventually, the concept of molding and pressing jars and bottles replaced the earlier methods and the quality of the glassware improved.

It began to be possible to produce glasses which were reasonably transparent, although usually still filled with bubbles and other flaws. The invention of glass blowing around the first century B.C. generated a greatly expanded range of applications for glasses. The quality of glass jars and bottles improved dramatically, glass drinking vessels became popular, and the first clear sheet glasses became available; which eventually allowed the construction of buildings with enclosed windows. Coloured glasses came into common use, with techniques for production of many colours regarded as family secrets, to be passed on from generation to generation of artisans. The method for producing red glasses by inclusion of gold in the melt, for example, was discovered and then lost, only to be rediscovered hundreds of years later. The combination of the discovery of many new colourants with the invention of glass blowing eventually led to the magnificent stained glass windows of so many of the great cathedrals of Europe and the Near East.

The advent of the Age of Technology created many new opportunities for the application of glasses. The evolution of chemistry from the secretive practices of alchemists searching for the philosopher’s stone, to a profession involving millions of workers worldwide was strongly influenced by the invention of chemically-resistant borosilicate glasses. Modern electronics became a reality with the invention of glass vacuum tubes, which evolved into the monitors for our computers and the televisions we watch every day.

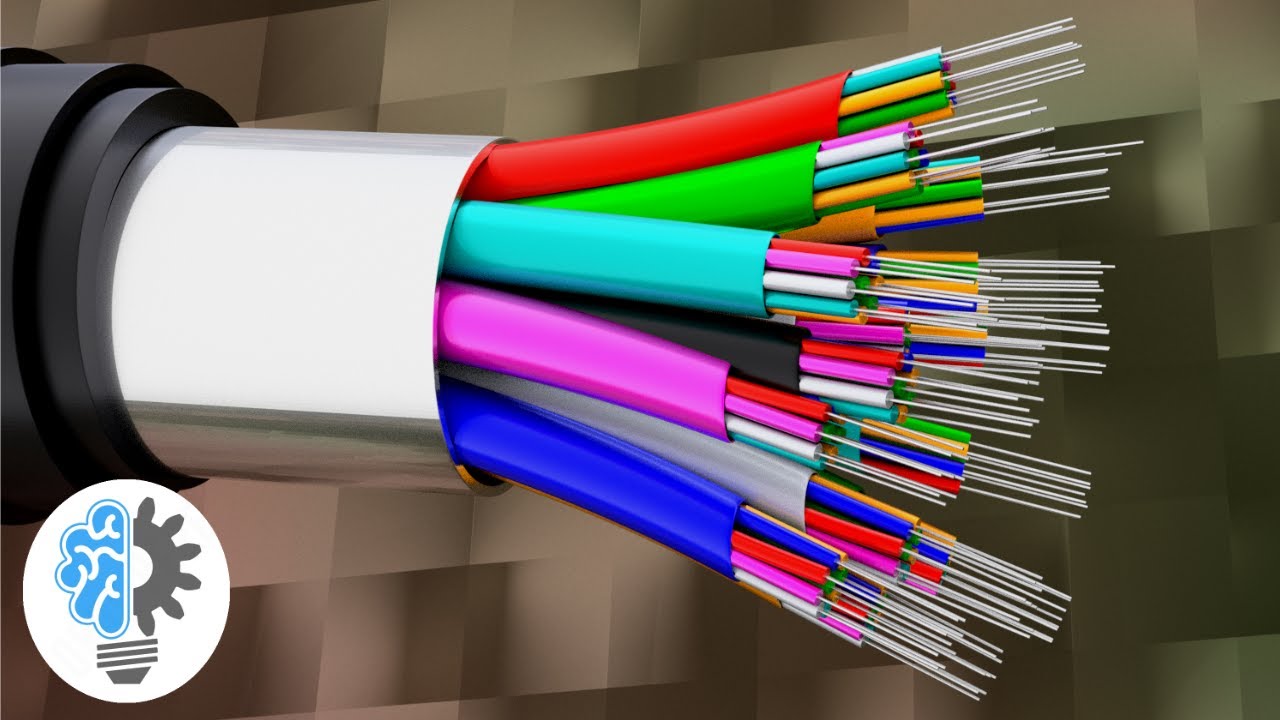

Recently, the development of glass optical fibers has revolutionized the telecommunications industry, with fibres replacing copper wires and radically expanding our ability to transmit flaw-free data throughout the world. Unlike many other materials, glasses are also aesthetically pleasing to an extent which far transcends their mundane applications as drinking vessels and ashtrays, windows and beer bottles, and many other everyday uses.

Why are we so delighted with a lead crystal chandelier or a fine crystal goblet? Why do we find glass sculptures in so many art museums? Why are the stained glass windows of the great cathedrals so entrancing? What aspects of objects made of glass make them so desirable for their beauty, as well as their more pragmatic uses? The answers to these questions may lie in the ability of glasses to transmit light. Very few materials exist in nature which are transparent to visible light. Metals are opaque, as are virtually all natural organic materials. Many liquids are transparent, but they are transient in nature, without the enduring qualities we desire in our possessions.

A list of the few transparent natural solids includes diamonds, emeralds, rubies, and many other precious and semi-precious stones. It is difficult to think of a naturally transparent solid which is not highly valued for its transparency and brilliance. Our heritage as humans would seem to provide a bias toward placing a high value on such objects. We are still fascinated by “bright, shiny objects.”

Glasses Defined

|

| Amorphous structure. PC: UNSW |

What is a “glass”? The glasses used by mankind throughout most of our history have been based on silica(SiO2). Is silica a required component of a glass? Since we can form an almost limitless number of inorganic glasses which do not contain silica, the answer is obviously, “No, silica is not a required component of a glass.”

Glasses are traditionally formed by cooling from a melt. Is melting a requirement for glass formation? No, we can form glasses by vapour deposition, by sol-gel processing of solutions, and by neutron irradiation of crystalline materials. Most traditional glasses are inorganic and non-metallic. We currently use a vast number of organic glasses. Metallic glasses are becoming more common with every passing year.

Obviously the chemical nature of the material cannot be used to define a glass. What, then, is required in the definition of a glass? All glasses found to date share two common characteristics. First, no glass has a long range, periodic atomic arrangement. And even more importantly, every glass exhibits time-dependent glass transformation behaviour. This behaviour occurs over a temperature range known as the glass transformation region.

A glass can thus be defined as “an amorphous solid completely lacking in long range, periodic atomic structure, and exhibiting a region of glass transformation behaviour.” Any material, inorganic, organic, or metallic, formed by any technique, which exhibits glass transformation behaviour is a glass. Glasses belong to the broader classification of ceramic materials: compounds between metallic and inorganic elements.

Properties and Uses

|

| Laboratory glass containers. PC: UNSW |

The major properties of glass are that:

- It is transparent

- Easy to fabricate

Below are some typical uses of glass in our world today:

- In art work without imparting an engineering property

- Laboratory equipment

- Transportation equipment

- Various types of kitchenware

- In modern architecture and building parts

- All types of screens

- In optics: telescopes, fibre optic cables

- Reinforcement material such as fibreglass

- Table tops

- Bottles - all shapes, size and colour

Additional Pictures

|

| Glass in architecture. PC: theconstructor |

|

| Glass model of a space shuttle. PC: castglass |

|

| Glass Kitchenware. PC: Explore India |

FunFact: Glasses can be recycled endless times and still maintain its properties .

On our next post on glasses, we will cover a more technical detail into these fascinating materials. Kindly stay tuned.

Here is a 2019 psychological superhero thriller film movie titled, Glass. Check it out.

Here is a 2019 psychological superhero thriller film movie titled, Glass. Check it out.

Comments

Post a Comment